LMT #139: Chhehrata, Amritsar City, India – Rana Behal

Rana Behal

Association of Indian Labour Historians and Retired Associate Professor of History, Deshbandhu College, New Delhi

On 6 June 2025 The Tribune, a well-known Chandigarh newspaper, published a story to mark May Day on 1 May 2025 ‘Chhehrata: From Industrial hub of forgotten township’ that appears to be a nostalgic and an obituary piece by Manmeet Singh Gill who wrote: ‘Once a thriving industrial township with a distinct identity, Chheharta’s story is now one of decline and neglect. Located on the outskirts of the holy city of Amritsar (home to the Golden Temple, the holiest site of the Sikh religion), Chheharta was a bustling hub, home to over a dozen large mills and numerous small-scale factories, power looms and handlooms.’ Chheharta is a suburban town located 7 km west of Amritsar city (state of Punjab), India, on the Grant Trunk Road leading to the Pakistan border.

Chheharta had a tradition of vibrant labour movements and trade union activities during 1930s and 1940s. Textile Workers Union was formed in 1944 and prior to that there were Labour Federations. The All India Trade Union Congress (AITUC) was present in Amritsar prior to 1947. The Communist Party of India was very active in the region. Most of the mazdoors (Punjabi term for workers) before partition were Muslims from the outskirt of the city and some Sikhs and Hindus from its agrarian hinterland. However, the Partition of the Indian subcontinent in 1947 was a traumatic shock to the city. The large-scale sectarian violence seriously affected industrial and commercial enterprises. The vast majority of Muslim mazdoors were forced to leave for Pakistan, depriving the industry its labour force. However, the influx of Hindu and Sikh refugees from Pakistan partly replaced the Muslim mazdoors along with the existing local labour that helped the resurgence of industrial activity. In the following decades many migrants from Himachal, UP and Bihar became part of this labour force in Chheharta industrial complex. Many migrants who came from UP and Bihar belong to the lower caste communities.

There was a resurgent of industrial activities during the next three decades after the Partition in Chhehrata. A diverse range of goods began to be manufactured and textiles, including woolen fabric, cotton, silk, carpets and shawls, were the most prominent among all the industrial enterprises in Amritsar. Textile mills became the dominated Chhehrta industrial space. The trade unions and labour activities again picked up.

All India Trade Union Congress (controlled by the Communist party of India) played an important role in organizing the mazdoors to fight for their rights.

Independent India’s new ruling party Indian National Congress also set up Indian National Trade Union Congress (INTUC).

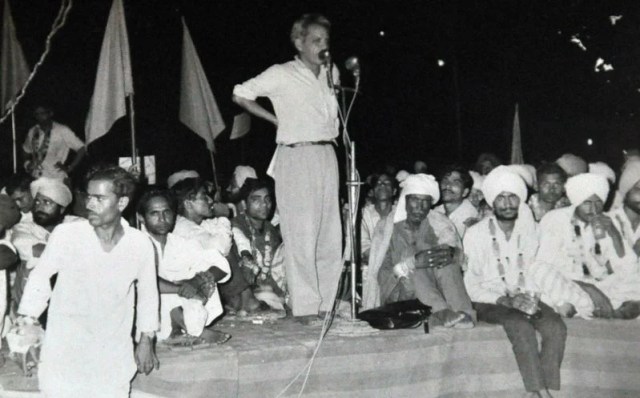

The mazdoor struggle during the second half of twentieth century in Chhehrata is intertwined with the legendry communist trade union couple Comrades Satya Pal Dang and Vimla Dang. Both came from middle class background and became involved with communist movement during their college days in Lahore before Independence. They came to Amritsar in 1952 as a part of AITUC and remained committed to mazdoor struggle for over six decades till the end of their lives. Their popularity among the mazdoors is reflected in both becoming President of Chhehrata Municipal Committee at different times. Vimla Dang was single handedly responsible for upstaging women workers and their families in Chhehrata labour movements. She organized Istri Sabha for championing the cause of women who supported mazdoor strikes by their participation and organizing food during their strikes. After the massacre of Sikhs in 1984 in Northern India, she travelled across the country raising funds for the maintenance of Sikh widows and their families. They lived and remained integral part of working-class neighbourhood in Chhehrata in a very simple frugal manner.

Yet another equally important AITUC leader, though less talked about, was Comrade Parduman Singh who, along with Dangs, was an integral part of organizing collective strikes of Textile Workers in 1955 and 1965 that successfully forced the employers to accept their demands for shorter working hours, higher wages, leave, bonus, equal wages to women workers and reinstatement of workers who were punished for participating in these strikes. He penned down and published the history of AITUC in Punajbi language to commemorate its 25 years in Amritsar in 1981. During the course of mazdoor struggle, both leaders, along with hundreds of workers faced severe state repression in the form of jail sentences or went underground to escape it.

While Dangs and Parduman came from educated middle class background and their lives and work are documented, there are many activists and mazdoors who have remained invisible despite their long term association and commitment with struggles in Chhehrata. Some of them also came from marginalised and lower caste back ground. I will briefly highlight stories of a few select workers who participated in mazdoor struggles and have continually remained associated in present times. Comrade Jagdish Sharma of AITUC, came to India as a teenage refugee after 1947. After four to five years of uncertain livelihood and wondering around refugee camps in Punjab, he found employment as a mazdoor in a textile mill in Chheharta in 1951. During the twenty years as a textile worker he became involved in the communist movement and finally became a full time worker of AITUC in 1971. For three quarters of a century he has remained a committed communist worker and trade union activist with conviction. He and his family shared working-class quarters. He recalls ‘like many others I was also influenced with communist ideas and activists. Ever since I became a mazdoor I have been and remained a communist. I never looked in any other direction ever, not even in my dreams.’ Now in his late 80s, though slow down, he remains a full time committed communist worker of AITUC. From his razor sharp memory I learnt many aspects and anecdotal accounts of mazdoor struggle and state repression in 1955, 1965 and 1972.

Kawanljit Singh, former worker and communist labour activist and now in his 70s, recalls his life as a worker and an activist: ‘Textile work was a very important business those days. I started working in 1962 in Radhakrishen Harbanslal textile mill and worked there for a long time. Workers came from the city, nearby villages and even some migrants. I learnt the work on the machine from some guru in the mill while working there. Those days working in the textile mill was considered very good.’

Comrade Barjinder of Communist Party of India Marxist (CPI M, a breakaway new group) was nostalgic of the heydays of the dominant mazdoor struggles of the 1960s and 1970s ‘The mill workers enjoyed respect and were proud of their status as workers. ‘My father worked on power looms in a textile factory. Power loom work paid better wages those days. He attributed this to the presence of strong mazdoor jathebandis (organization) to fight for better wages.’

Comrade Amarjit Singh Assal, the current secretary of AITUC in Putlighar came from a family of landless Dalits. His marginalised background attracted him to communism. His father was a labourers who carried bags of grain at the station in Patti. Education opportunity brought me to Chhehrata in 1977 and there I connected with CPI student wing, AISF. ‘Since 1983 I have been involved with the Party at regular basis.’ By this time mazdoor struggle and trade union situation were at a low ebb, a crucial juncture of its survival. As party secretary he is familiar with its history as well as the current situation of trade union movement in the industrial town.

Similarly, Mohinder Sigh Walia, a former railways worker, has been associated with AITUC for forty years. Even after retirement he continues to work with the Party without any financial benefits. ‘Working class politics and its activities expanded sending clear signals to the employers against arbitrary dismissals or non-compliance of labour laws,’ he mentioned. But he, along with his colleagues, is disappointed with the decline of trade unions and closure of mills. He challenges the allegations that mazdoor politics is responsible for it. ‘We had fought for the passing of labour laws and now we struggle for the implementation of those laws. The reason for closing mills were different. The factory lands have become very valuable and the owners found more profitable business by selling these mills.

The decade of 1980s that experienced a sharp industrial decline in well-known cities like Bombay, Ahmadabad and Kanpur The decline of Chhehrata industrial town began around the same time due to the emergence of Sikh militancy in Punjab politics. Amritsar became the major Centre of armed conflict between Sikh militants and the India State. The atmosphere of violence let loose by the militants and state, affected every day life of people in Amritsar. Sikh militants also targeted trade unions and started extraction from mill owners. The declining trends were further accentuated by the adoption of neo-liberal economic policies by India State at the beginning of 1990s. Many industrial and commercial entrepreneurs left the city and relocated in other parts of India.

I introduced this paper with the Tribune newspaper article on the marginalized situation of Chhehrata industrial township. In 2017, while driving me on his motor cycle on the Grant Trunk Road in Chhehrta, Comrade Barjinder pointed to both sides of the road, where once many great mills dominated the landscape of the entire stretch from Chhehrta to Putlighar chowk. These are now nostalgic memories only, as the entire landscape of industrial township has been physically transformed into shopping malls, hotels, fancy showrooms selling automobiles, private medical hospitals, private educational and training institutions etc. The mills with their chimneys and its workers have disappeared. The working-class presence in the neighbourhoods have shrunk. The so-called labour reforms introduced by illiberal regime have taken away the labour rights won over decades of struggles and consequently, weakened the working-class organization across India. While standing in front of AITUC office in Putlighar I can see only one symbolic big chimney that has survived the turbulence times.

The current photo of AITUC Office in Putlighar, Chheharta. A symbol of once a very Powerful Trade Union in Chheharta.

To learn more:

- Portelli, ‘The Peculiarities of Oral History’ in History Workshop Journal. Vol. 12. No. 1, 1981, pp. 96-107.

- Praduman Singh, Amritsar di Mazdoor Tahireek Da Sankhep Itihas: Textile Mazdoor Ekta Union Amritsar de Panjhi Saal 1955-1980 [A Short History of Labour in Amritsar: 25 Years of Textile Unity Union in Amritsar], (Amritsar: Textile Mazdoor Ekta Union, 1981); Amritsar District Gazetteer 1971.

- Bashir Ahmed Bakhtiar, ‘Labour Movement and Me’ translated from Urdu to English by Ahmad Azhar in Ravi Ahuja (ed.) Working Lives & Worker Militancy: The Politics of Labour in Colonial India (New Delhi: Tulika books, 2013), pp. 274-328.

- Chitra Joshi, Lost Worlds: Indian Labour and Its Forgotten Histories (New Delhi: Permanent Black), 2003.

Cover image credit: Cover image credits: A file photograph of CPI leader Satya Pal Dang addressing a workers’ gathering in Punjab. Available at: https://www.tribuneindia.com/news/in-depth/the-dangs-of-chheharta-legacy-that-endures/